So beautiful I watched it twice.

Category: about writing

It’s a Plot

Larry Brooks at Storyfix has a good explanation of plot, and why stories need one [Novelists: Two Empowering Little Mind-Models That Just Might Change Everything For You]

Plot is the creation of character and dramatic dynamics that lead to, point toward, that call for, that require… resolution.

A story in any genre (other than literary) that asks the reader simply to observe a character or his/her life… a story that episodically tells the life story of a fictional character without it leading to something that must be resolved… a story that exists to show us eras of a character’s life, novels that read like a collection of shorter stories, moving from one period in that life to to the next… if they are in any genre other than “literary fiction,” the project is at risk.

One of those just crossed my desk, from a graduation of an MFA program, where the word “plot” is likely never to uttered aloud. It was a YA, and it was nothing other than “the adventures of” the hero. Unconnected “stuff that happened” to this protagonist, peppered with backstory and inner landscape.

There are magic words found at the bottom line of this issue: genre fiction needs to give readers something to root for… rather than just something to observe.

Ask your reader to care about where it is all headed. To root for someone and/or something, to fear something or someone that is antagonistic blocking your hero’s path along the core story spine. To engage them emotionally, not just because they sympathize with the hero, but because feel and relate to the stakes of the story.

Genre fiction is the antithesis of “slice of life” storytelling.

Plots are driven by stakes. Even in YA and romance, where any and all of the available sub-genres are available fodder.

Without plot, writing is little more than a literary exercise. That may be entertaining to the writer, and it may be impressive to literature professors, but if it doesn’t engage readers, then what’s the point?

Interesting read: Charts and Diagrams Drawn by Famous Authors

Flavorwire: Charts and Diagrams Drawn by Famous Authors

I have a stash of these types of images in my writing reference folder, but Flavorwire links to some I haven’t seen yet. Diving down into the individual [via] links to the original articles on each chart is a must – Without it I wouldn’t have landed on this cool page page of Faulkner’s maps of Yoknapatawpha County.

Pretty much everyone includes this chart of JK Rowling’s characters and stories, but I haven’t posted it on any of my own writing yet, so here you go:

This Vonnegut video they include is nice, too:

Charles Dickens and Character Names in Bleak House

Bleak House is a giant tome (it clocks in at 360,947 words!) and is regarded as one of Charles Dicken’s finest works.

One of the things that I’ve always loved about Charles Dickens’ books which struck me again while watching the 2005 BBC series of Bleak House was how evocative Dickens’ characters & places names are, and how they helps shape our perception of personalities and appearances:

- Bleak House – as portrayed in the series, the seat of the Jardyce estate is bright and beautiful, but the inhabitants are living under strained circumstances and a looming sense of uncertain fate.

- Chesney Wold – Home of the Sir Leicester Dedlock & Lady Dedlock. A wold is an ancient word for forest and not uncommon for a place name, but it also sounds like mold and decay.

- Tom-All-Alone’s – The grim, dirty, disease-festering, terrible slum street where various characters seek refuge. I had the impression that it was an asylum for the homeless when viewing the BBC series, but despite the name, it wasn’t an organized shelter.

- John Jarndyce – One of the claimants in the contested legal case, the name of which is repeated over and over – “Jarndyce vs. Jarndyce” evokes jaundice, a symptom of longstanding illness.

- Esther Summerson – the bright spot of the story and the heroine.

- Lady Dedlock (Honoria Barbary) – Her character is in a “deadlocked” situation, legally and emotionally. In the series, we don’t hear her first name until the final hour, when her character’s scandal is finally revealed – her honor having been lost in ruins when her illegitimate child is revealed. Not sure if that late reveal is true within the book.

- Richard Carstone – one of the “wards in Jarndyce” – the claimants to the legal case who hope to inherit a fortune.

- Ada Clare – the other “ward in Jarndyce” – a title frequently used in substitute for Ada & Richard’s names, and one that that makes the two young people sound like they are imprisoned in an asylum.

- Harold Skimpole – a leech and hanger-on of John Jarndyce and a lesser villain, he skims money wherever he goes.

- Lawrence Boythorn – the thorn in Leicester Dedlock’s side.

- Sir Leicester Dedlock – like his wife, in a deadlocked situation

- Mr. Tulkinghorn – the villain of the book; his name makes him sound like a maurauding beast

- Mr. Snagsby – clerk who seems to be caught up against his will.

- Miss Flite – keeper of numerous birds, and a flighty, eccentric woman

- Mr. William Guppy – law clerk and an insignificant wet fish

- Inspector Bucket – a blustering police officer

- Mr. George (George Rouncewell) – military buddy of Hawdon, Mr. George drops his last name due to estrangement from his family.

- Caddy Jellyby – named literally after a tea caddy, she is ordered about by her mother.

- Krook – pretty straight-forward; his obsessive hoarding of papers essential steals everyones’ lives.

- Jo – an orphan boy who has not much to his name, literally and figuratively.

- Allan Woodcourt – an upright, kind many who is courting Ester Summerson

- Grandfather Smallweed – a small, twisted man and noxious weed who complicated everyone’s lives

- Mr. Vholes – a foraging rodent of a man.

- Conversation Kenge – “His chief foible is his love of grand, portentous, and empty rhetoric” according to wikipedia, and I couldn’t have put that better.

- Mr. Gridley – a victim of Chancery who dies without his legal circumstances resolved. Gridley reminds me of gridlock.

- Mr. Nemo (Latin for “nobody”; alias of Captain James Hawdon) – a man who lost his name completely.

- Prince Turveydrop – the dancing master whose name evokes a spinning top.

- Mrs. Rouncewell – the housekeeper at Chesney Wold. “a fine old lady, handsome, stately, wonderfully neat” – she seems very well-rounded.

- Phil Squod – Mr. George’s friend and an invalid with several disabilities due to working class labors.

- Volumnia Dedlock – sixty-year old poor relation of Sir Leicester Dedlock “Lapsing then out of date, and being considered to bore mankind by her vocal performances”

And of course there are the names of Miss Flite’s caged birds who will be released “on the day of Judgement” which is meant to make us think “the day the Lord returns” but is actually when Jarndyce & Jarndyce will finally be settled. The bird’s names can be grouped into classes, according to J. Hillis Miller:

- the victims of Chancery – Hope, Joy, Youth, Peace, Rest, Life,

- Chancery’s effects – Dust, Ashes, Waste, Want, Ruin, Despair, Madness, Death

- Chancery’s qualities or tools – Cunning, Folly, Words, Wigs, Rags, Sheepskin, Plunder, Precedent, Jargon, Gammon, and Spinach (or Spinnage an earlier spelling of Spinach. Dickens uses the phrase “Gammon and spinnage” to mean “Gammon and nonsense” in David Copperfield as well.)

- and finally, two new birds symbolic of Richard & Ada “the Wards in Jarndyce.”

We had a short discussion in my recent writing group about unusual Puritan Names when we discussed the character names in my own work-in-progress – Fidelia being one of the two main characters – a name I chose specifically because themes of the book circle around truth and secrets and when those secrets should be revealed and to whom. Puritans enjoyed giving their children names like “Preserved” or “Thankful” or “Faithful” or “Clemency” in hopes that the name would shape the character of the child to be virtuous and upright.

Many Puritan names are over the top, (“Humiliation”, “Abstinence” & “Sorry-for-sin” or “Job-rakt-out-of-the-asshes” are good examples) but names like Honoria or Grace or Fidelia are beautiful and wouldn’t be out of place for girls today. I’m not so certain that Increase or Stalwart or Anger or Conversation would be ideal for boys, but I could see enterprising hipster parents adopting something along those lines in the future.

It might be fairly heavy-handed and Dickensian to name all my characters this way, but I do enjoy the amount of thought and care that Dickens put into appellations. “Thought” and “Care” would be pretty cool character names, now that I think of it.

Literary Names: Personal Names in English Literature

Miller, J. Hillis. “Interpretation in Dickens’s Bleak House” in Victorian Subjects (Durham: Durham University Press, 1991)

Naming and Violence in Bleak House

Curiosities of Puritan nomenclature (1888) by Charles W. Bardsley; 1888; Chatto and Windus, London

Ditching Dickensian

David Foster Wallace: This is Water

A condensed version of the commencement speech David Foster Wallace gave at Kenyon College in 2005, set to video. You can read the whole of the commencement address here at the Economist’s Intelligent Life.

And the so-called real world will not discourage you from operating on your default settings, because the so-called real world of men and money and power hums merrily along in a pool of fear and anger and frustration and craving and worship of self. Our own present culture has harnessed these forces in ways that have yielded extraordinary wealth and comfort and personal freedom. The freedom all to be lords of our tiny skull-sized kingdoms, alone at the centre of all creation. This kind of freedom has much to recommend it. But of course there are all different kinds of freedom, and the kind that is most precious you will not hear much talk about much in the great outside world of wanting and achieving…. The really important kind of freedom involves attention and awareness and discipline, and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them over and over in myriad petty, unsexy ways every day.

…

It is about the real value of a real education, which has almost nothing to do with knowledge, and everything to do with simple awareness; awareness of what is so real and essential, so hidden in plain sight all around us, all the time, that we have to keep reminding ourselves over and over:

“This is water.”

“This is water.”

It is unimaginably hard to do this, to stay conscious and alive in the adult world day in and day out. Which means yet another grand cliché turns out to be true: your education really IS the job of a lifetime. And it commences: now.

I wish you way more than luck.

List of linguistic example sentences

Via wikipedia – List of linguistic example sentences

From the “grammar is fun” section of wikipedia, the page includes sentences that explain:

Lexical ambiguity:

Will Will will Will’s will to Will? (Will Will [a person] will [bequeath] Will’s [second person] will [a document] to Will [a third person]? Alternatively, “Will Will will Will’s will?” Also, why do all these guys name Will know each other and can’t someone go by Bill and someone by William? Or maybe Larry?)

Syntactic ambiguity:

I saw the man with the binoculars. (Who has the binoculars? Me, or the man?)

Syntactic ambiguity, incrementality, and Local Coherence:

The boat floated down the river sank. (As in – the boat which had been floated down the river sank.)

Scope ambiguity and anaphora resolution:

Somewhere in Britain, some woman has a child every thirty seconds. (Every thirty seconds, a woman somewhere in Britain has a child. But not the same woman over and over, because that would be really weird.)

Embedding:

The rat the cat the dog bit chased escaped. (The cat the dog bit chased the rat that escaped. I think.)

Order of adjectives:

The red big balloon. (Yeah, why does big always go first?)

The Amazing, Possibly True Adventures of Catman Keeley and His Corporate Hoboes

From Mother Jones: The Amazing, Possibly True Adventures of Catman Keeley and His Corporate Hoboes.

A long article about a rich adventurer dude name Bo Keeley who leads corporate honchos on adventure travel like a goddamned hobo. This is what rich white guys do when they have too much money and free time – pretend to be the rest of us. The article is entertaining because the writer is, though, so it’s worth a read.

The first thing you’ll discover about Bo Keeley is that his Wikipedia page reads like Indiana Jones. “Bo’s Wikipedia entry reads like Indiana Jones,” states the about-the-author page of one of his most recent books, which details his past as a veterinarian, a former national racquetball champion, and the most-requested substitute teacher ever to be fired during a playground war in Blythe, California. It’s not an entirely fair comparison—did Henry Jones Jr. ever claim to have guided “twenty Brazilian evangelists with a penlight from a jungle bus crash” or chased “rhinoceros horn smugglers after being deputized and armed with a pistol in Namibia”? Many of these claims are sourced to Keeley himself, making the page a matter of some controversy. But it’s that muddy trench between man and myth that makes it such an alluring document. As one Wikipedia editor put it, “Due to the uniqueness of the individual, some hyperbole is understandable.”

Parataxis

Parataxis – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Parataxis is a literary technique, in writing or speaking, that favors short, simple sentences, with the use of coordinating rather than subordinating conjunctions.

Examples

Perhaps the best-known use of parataxis is Julius Caesar’s famous quote, “Veni, vidi, vici” or, “I came, I saw, I conquered”. An extreme example is the immortal Mr. Jingle’s speech in Chapter 2 of The Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens.‘Come along, then,’ said he of the green coat, lugging Mr. Pickwick after him by main force, and talking the whole way. ‘Here, No. 924, take your fare, and take yourself off—respectable gentleman—know him well—none of your nonsense—this way, sir—where’s your friends?—all a mistake, I see—never mind—accidents will happen—best regulated families—never say die—down upon your luck—Pull him UP—Put that in his pipe—like the flavour—damned rascals.’ And with a lengthened string of similar broken sentences, delivered with extraordinary volubility, the stranger led the way to the traveller’s waiting-room, whither he was closely followed by Mr. Pickwick and his disciples.

Perhaps an even more extreme proponent of the form was Samuel Beckett. The opening to his monologue “Not I” is a classic example:

” . out . . . into this world . . . this world . . . tiny little thing . . . before its time . . . in a godfor– . . . what? . . girl? . . yes . . . tiny little girl . . . into this . . . out into this . . . before her time . . . godforsaken hole called . . . called . . . no matter . . . parents unknown . . . unheard of . . . he having vanished . . . thin air . . . no sooner buttoned up his breeches . . . she similarly . . . eight months later . . . almost to the tick . . . so no love . . . spared that . . . no love such as normally vented on the . . . speechless infant . . . in the home . . . no . . . nor indeed for that matter any of any kind . . . no love of any kind . . . at any subsequent stage” and so on.

Although the use of ellipses here arguably prevents it from being seen as a classic example of parataxis, as a spoken text it operates in precisely that way. Other examples by Beckett would include large chunks of Lucky’s famous speech in Waiting for Godot.

Iron Writer Challenge: Accepted

I signed up for the Iron Writer Challenge, and will be competing on February 12th. How it works – 5 authors each write a 500 word flash fiction story in a 4 day span of time including 4 required elements (example: 1968 Elvis Presley Comeback Special, Someone mowing/cutting grass, A note left on a car, Argyle socks) then compete against each other for the most votes & judges approval.

I’m hoping to brush up on my short fiction writing skills and have some content to add to my short fiction page as well.

Fiction Writer’s Cheat Sheet

Cribbed from the internet – It appears to be the creation of author Emily Breder.

Quotes: no one loves chili dogs that much

Gillian Flynn in Gone Girl:

Men always say that as the defining compliment, don’t they? She’s a cool girl. Being the Cool Girl means I am a hot, brilliant, funny woman who adores football, poker, dirty jokes, and burping, who plays video games, drinks cheap beer, loves threesomes and anal sex, and jams hot dogs and hamburgers into her mouth like she’s hosting the world’s biggest culinary gang bang while somehow maintaining a size 2, because Cool Girls are above all hot. Hot and understanding. Cool Girls never get angry; they only smile in a chagrined, loving manner and let their men do whatever they want. Go ahead, shit on me, I don’t mind, I’m the Cool Girl.

Men actually think this girl exists. Maybe they’re fooled because so many women are willing to pretend to be this girl. For a long time Cool Girl offended me. I used to see men – friends, coworkers, strangers – giddy over these awful pretender women, and I’d want to sit these men down and calmly say: You are not dating a woman, you are dating a woman who has watched too many movies written by socially awkward men who’d like to believe that this kind of woman exists and might kiss them. I’d want to grab the poor guy by his lapels or messenger bag and say: The bitch doesn’t really love chili dogs that much – no one loves chili dogs that much! And the Cool Girls are even more pathetic: They’re not even pretending to be the woman they want to be, they’re pretending to be the woman a man wants them to be. Oh, and if you’re not a Cool Girl, I beg you not to believe that your man doesn’t want the Cool Girl. It may be a slightly different version – maybe he’s a vegetarian, so Cool Girl loves seitan and is great with dogs; or maybe he’s a hipster artist, so Cool Girl is a tattooed, bespectacled nerd who loves comics. There are variations to the window dressing, but believe me, he wants Cool Girl, who is basically the girl who likes every fucking thing he likes and doesn’t ever complain. (How do you know you’re not Cool Girl? Because he says things like: “I like strong women.” If he says that to you, he will at some point fuck someone else. Because “I like strong women” is code for “I hate strong women.”)

Quotes: Distant Fog

Lemony Snicket:

I will love you as a thief loves a gallery and as a crow loves a murder, as a cloud loves bats and as a range loves braes. I will love you as misfortune loves orphans, as fire loves innocence and as justice loves to sit and watch while everything goes wrong. I will love you as a battlefield loves young men and as peppermints love your allergies, and I will love you as the banana peel loves the shoe of a man who was just struck by a shingle falling off a house. I will love you as a volunteer fire department loves rushing into burning buildings and as burning buildings love to chase them back out, and as a parachute loves to leave a blimp and as a blimp operator loves to chase after it.

I will love you as a dagger loves a certain person’s back, and as a certain person loves to wear dagger proof tunics, and as a dagger proof tunic loves to go to a certain dry cleaning facility, and how a certain employee of a dry cleaning facility loves to stay up late with a pair of binoculars, watching a dagger factory for hours in the hopes of catching a burglar, and as a burglar loves sneaking up behind people with binoculars, suddenly realizing that she has left her dagger at home. I will love you as a drawer loves a secret compartment, and as a secret compartment loves a secret, and as a secret loves to make a person gasp, and as a gasping person loves a glass of brandy to calm their nerves, and as a glass of brandy loves to shatter on the floor, and as the noise of glass shattering loves to make someone else gasp, and as someone else gasping loves a nearby desk to lean against, even if leaning against it presses a lever that loves to open a drawer and reveal a secret compartment. I will love you until all such compartments are discovered and opened, and until all the secrets have gone gasping into the world. I will love you until all the codes and hearts have been broken and until every anagram and egg has been unscrambled.

I will love you until every fire is extinguised and until every home is rebuilt from the handsomest and most susceptible of woods, and until every criminal is handcuffed by the laziest of policemen. I will love until M. hates snakes and J. hates grammar, and I will love you until C. realizes S. is not worthy of his love and N. realizes he is not worthy of the V. I will love you until the bird hates a nest and the worm hates an apple, and until the apple hates a tree and the tree hates a nest, and until a bird hates a tree and an apple hates a nest, although honestly I cannot imagine that last occurrence no matter how hard I try. I will love you as we grow older, which has just happened, and has happened again, and happened several days ago, continuously, and then several years before that, and will continue to happen as the spinning hands of every clock and the flipping pages of every calendar mark the passage of time, except for the clocks that people have forgotten to wind and the calendars that people have forgotten to place in a highly visible area. I will love you as we find ourselves farther and farther from one another, where we once we were so close that we could slip the curved straw, and the long, slender spoon, between our lips and fingers respectively.

I will love you until the chances of us running into one another slip from slim to zero, and until your face is fogged by distant memory, and your memory faced by distant fog, and your fog memorized by a distant face, and your distance distanced by the memorized memory of a foggy fog. I will love you no matter where you go and who you see, no matter where you avoid and who you don’t see, and no matter who sees you avoiding where you go. I will love you no matter what happens to you, and no matter how I discover what happens to you, and no matter what happens to me as I discover this, and now matter how I am discovered after what happens to me as I am discovering this.

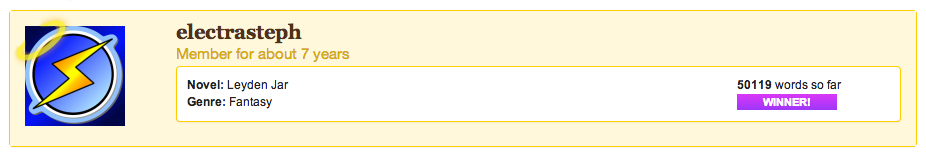

NaNoWriMo 2014 Winner

This is my fourth consecutive win. It sort of feels a little less-satisfying that the others. For one thing, I’m writing something that’s intensely personal, so I kind of felt pretty drained by it. Also, there was a lot of research involved because it’s historical fiction, so even when I wasn’t writing, the topic was all-consuming of my time. I have a bibliography with 20+ titles on it, and links to hundreds of websites. I have a web folder full of images, maps, and two different pinterest pages, one for the novel and one for one of the main characters.

Another reason I feel drained is because it isn’t done – and I have two other unfinished novels that I haven’t been able to get past the 75% mark. This novel I plotted out far more than the others, and I feel like it has a better chance of having some resonance, but the last two days of writing were excruciating and involved me basically throwing junk on the page. I’m so far off my outline it isn’t even funny, and I definitely need to regroup.

NaNoWriMo is great for getting a ton written in a short amount of time and staying motivated. It’s terrible for causing burnout. And all my efforts to pick up the threads and try to finish at a less punishing pace in the months that follow NaNoWriMo have fallen into failure in the past.

I’m committed to changing that scenario this year and getting the book to something readable to others. But I also need to take the month to do some reading as well.

So basically, I’m optimistic, but dazed. Which is probably normal for me, right?

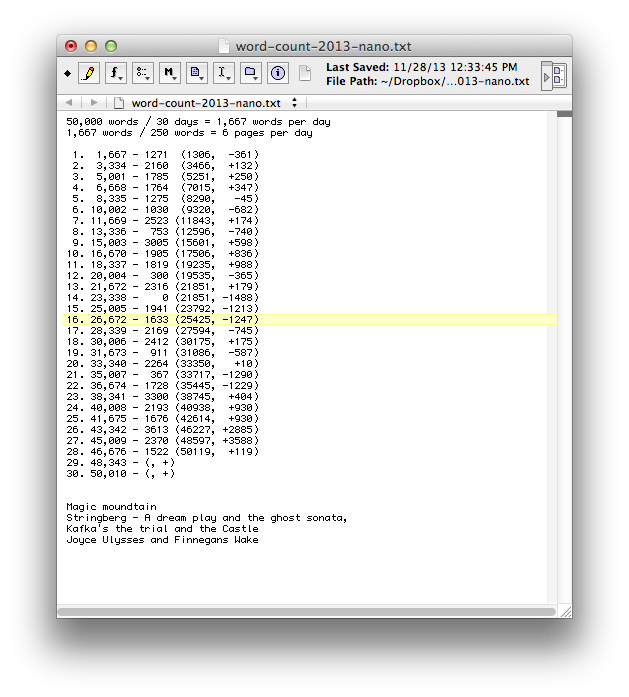

The running tally of my word count this year. Compared to last year, I was far behind most of the time, rather than ahead. I didn’t plan my resources properly and I let a lot of distractions in the door this year, which didn’t help.

1. 1,667 - 4218 (4218, +2551)

2. 3,334 - 1691 (5909, +2575)

3. 5,001 - 1060 (6969, +1968)

4. 6,668 - 1701 (8670, +2002)

5. 8,335 - 1051 (9721, +1386)

6. 10,002 - 126 (9847, -155)

7. 11,669 - 1031 (10878, -791)

8. 13,336 - 3922 (14800, +1464)

9. 15,003 - 1817 (16617, +1614)

10. 16,670 - 1762 (18358, +1688)

11. 18,337 - 0 (18358, +21)

12. 20,004 - 0 (18358, -1646)

13. 21,672 - 0 (18358, -3313)

14. 23,338 - 0 (18358, -4980)

15. 25,005 - 4720 (23078, -1927)

16. 26,672 - 3747 (26825, +153)

17. 28,339 - 1837 (28662, +323)

18. 30,006 - 638 (29300, -706)

19. 31,673 - 0 (29300, -2373)

20. 33,340 - 161 (29461, -3879)

21. 35,007 - 366 (29827, -5180)

22. 36,674 - 4782 (34586, -2088)

23. 38,341 - 2268 (36854, -1487)

24. 40,008 - 440 (37294, -2714)

25. 41,675 - 4656 (41950, +275)

26. 43,342 - 1734 (43684, +342)

27. 45,009 - 813 (44497, -512)

28. 46,676 - 23 (44520, -2156)

29. 48,343 - 2733 (47253, -1090)

30. 50,010 - 2747 (50179, +179)

Publisher’s Weekly: The Top 10 Essays Since 1950

From Publisher’s Weekly: The Top 10 Essays Since 1950.

Robert Atwan, the founder of The Best American Essays series, picks the 10 best essays of the postwar period. Links to the essays are provided when available.

Fortunately, when I worked with Joyce Carol Oates on The Best American Essays of the Century (that’s the last century, by the way), we weren’t restricted to ten selections. So to make my list of the top ten essays since 1950 less impossible, I decided to exclude all the great examples of New Journalism–Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, Michael Herr, and many others can be reserved for another list. I also decided to include only American writers, so such outstanding English-language essayists as Chris Arthur and Tim Robinson are missing, though they have appeared in The Best American Essays series. And I selected essays, not essayists. A list of the top ten essayists since 1950 would feature some different writers.

To my mind, the best essays are deeply personal (that doesn’t necessarily mean autobiographical) and deeply engaged with issues and ideas. And the best essays show that the name of the genre is also a verb, so they demonstrate a mind in process–reflecting, trying-out, essaying.

James Baldwin, “Notes of a Native Son” (originally appeared in Harper’s, 1955)

Norman Mailer, “The White Negro” (originally appeared in Dissent, 1957)

Susan Sontag, “Notes on ‘Camp’” (originally appeared in Partisan Review, 1964)

John McPhee, “The Search for Marvin Gardens” (originally appeared in The New Yorker, 1972) (subscription required).

Joan Didion, “The White Album” (originally appeared in New West, 1979)

Annie Dillard, “Total Eclipse” (originally appeared in Antaeus, 1982)

Phillip Lopate, “Against Joie de Vivre” (originally appeared in Ploughshares, 1986)

Edward Hoagland, “Heaven and Nature” (originally appeared in Harper’s, 1988)

Jo Ann Beard, “The Fourth State of Matter” (originally appeared in The New Yorker, 1996)

David Foster Wallace, “Consider the Lobster” (originally appeared in Gourmet, 2004) (Note: the electronic version from Gourmet magazine’s archives differs from the essay that appears in The Best American Essays and in his book, Consider the Lobster.)

Thirteen Ways of Looking at Greg Maddux

A really excellent essay by Jeremy Collins at SBNation.com – Thirteen Ways of Looking at Greg Maddux. Worth a read.

East of the Sun and West of the Moon

Wikipedia: “East of the Sun and West of the Moon” is a Norwegian folk tale.

The White Bear approaches a poor peasant and asks if he will give him his youngest daughter; in return, he will make the man rich. The girl is reluctant, so the peasant asks the bear to return, and persuades her in the meantime. The White Bear takes her off to a rich and enchanted castle. At night, he takes off his bear form in order to come to her bed as a man, although the lack of light means that she never sees him.

When she grows homesick, the bear agrees that she might go home as long as she agrees that she will never speak with her mother alone, but only when other people are about. At home, they welcome her, and her mother makes persistent attempts to speak with her alone, finally succeeding and persuading her to tell the whole tale. Hearing it, her mother insists that the White Bear must really be a troll, gives her some candles, and tells her to light them at night, to see what is sharing her bed.

The youngest daughter obeys, and finds he is a highly attractive prince, but she spills three drops of the melted tallow on him, waking him. He tells her that if she held out a year, he would have been free, but now he must go to his wicked stepmother, who enchanted him into this shape and lives in a castle east of the sun and west of the moon, and marry her hideous daughter, a troll princess.

In the morning, the youngest daughter finds that the palace has vanished. She sets out in search of him. Coming to a great mountain, she finds an old woman playing with a golden apple. The youngest daughter asks if she knows the way to the castle east of the sun and west of the moon. The old woman cannot tell her, but lends the youngest daughter a horse to reach a neighbor who might know, and gives her the apple. The neighbor is sitting outside another mountain, with a golden carding comb. She, also, does not know the way to the castle east of the sun and west of the moon, but lends the youngest daughter a horse to reach a neighbor who might know, and gives her the carding-comb. The third neighbor has a golden spinning wheel. She, also, does not know the way to the castle east of the sun and west of the moon, but lends the youngest daughter a horse to reach the East Wind and gives her the spinning wheel.

The East Wind has never been to the castle east of the sun and west of the moon, but his brother the West Wind might have, being stronger. He takes her to the West Wind. The West Wind does the same, bringing her to the South Wind; the South Wind does the same, bringing her to the North Wind. The North Wind reports that he once blew an aspen leaf there, and was exhausted after, but he will take her if she really wants to go. The youngest daughter does wish to go, and so he takes her there.

The next morning, the youngest daughter takes out the golden apple. The troll princess who was to marry the prince sees it and wants to buy it. The girl agrees, if she can spend the night with the prince. The troll princess agrees but gives the prince a sleeping drink, so that the youngest daughter cannot wake him. The same thing happens the next night, after the youngest daughter pays the troll princess with the gold carding-combs. During the girl’s attempts to wake the prince, her weeping and calling to him is overheard by some imprisoned townspeople in the castle, who tell the prince of it. On the third night, in return for the golden spinning wheel, the troll princess brings the drink, but the prince does not drink it, and so is awake for the youngest daughter’s visit.

The prince tells her how she can save him: He will declare that he will not marry anyone who cannot wash the tallow drops from his shirt since trolls, such as his stepmother and her daughter, the troll princess, cannot do it. So instead, he will call in the youngest daughter, and she will be able to do it, so she will marry him. The plan works, and the trolls, in a rage, burst. The prince and his bride free the prisoners captive in the castle, take the gold and silver within, and leave the castle east of the sun and west of the moon.

Powerful Essay on the World Trade Center Attacks

By Steve Kandell on Buzzfeed [The Worst Day Of My Life Is Now New York’s Hottest Tourist Attraction]:

The fact that everyone else here has VIP status grimly similar to mine is the lone saving grace; the prospect of experiencing this stroll down waking nightmare lane with tuned-out schoolkids or spectacle-seekers would be too much. There are FDNY T-shirts and search-and-rescue sweatshirts and no one quite makes eye contact with anyone else, and that’s just fine. I think now of every war memorial I ever yawned through on a class trip, how someone else’s past horror was my vacant diversion and maybe I learned something but I didn’t feel anything. Everyone should have a museum dedicated to the worst day of their life and be forced to attend it with a bunch of tourists from Denmark. Annotated divorce papers blown up and mounted, interactive exhibits detailing how your mom’s last round of chemo didn’t take, souvenir T-shirts emblazoned with your best friend’s last words before the car crash. And you should have to see for yourself how little your pain matters to a family of five who need to get some food before the kids melt down. Or maybe worse, watch it be co-opted by people who want, for whatever reason, to feel that connection so acutely.

Writing off Jennifer Weiner

I don’t know how it’s possible, but after reading this New Yorker profile “Written Off” by Rebecca Mead, I love Jennifer Weiner more than I did before reading it, although it’s widely being described as “a take-down” piece. The profile starts out fine, but about half-way through, the paragraph that starts “Weiner has also taken literary inspiration from her mother…” is the point where the whole thing just skates off the rails (Mead’s suggestion that Weiner’s lesbian characters are somehow anti-gay is bogus, small and unworthy of that publication) and Mead begins just coloring on the walls rather than finishing her work. I’m not sure whether I respect Mead’s audacity more for just saying “aw fuck it, I’m writing myself into a corner” in the middle of an article for The New Yorker, or The New Yorker’s for publishing it without fixing it, or apparently, even realizing it needs to be fixed.

This paragraph is so funny I had to get up and go to the bathroom and pee before I could finish:

A novel that tells of the coming of age of a young woman can command as much respect from the literary establishment as any other story. In 2013, Rachel Kushner was nominated for a National Book Award for her hard-edged exploration of this theme, “The Flamethrowers,” and the previous year Sheila Heti won accolades for her book “How Should a Person Be?,” even though it included both shopping and fucking. The novel, and the critical consensus around what is valued in a novel, has never excluded the emotional lives of women as proper subject matter. It could be argued that the exploration of the emotional lives of women has been the novel’s prime subject. Some of the most admired novels in the canon center on a plain, marginalized girl who achieves happiness through the discovery of romantic love and a realization of her worth. “My bride is here,” Mr. Rochester tells Jane Eyre, “because my equal is here, and my likeness.”

Emphasis very much mine. I can’t even with the Jane Eyre in a discussion of women in contemporary literature.

The thing that is almost entirely missing from this article is any detailed analysis of Jennifer Weiner’s case for re-thinking what is and what should be considered “literary merit.” Her critique is a serious (and valid) one, and not to be dismissed, but Mead attempts to ignore it almost completely, falling back on George Eliot’s 1856 essay to bolster the blinders she keeps, while ignoring the very points she lightly quotes about Weiner’s thoughts early on in the piece.

A loose paraphrasing of Weiner’s ideas:

- that the two great contemporary literary themes “white men doing great things or failing in the attempt” and “oppressed peoples struggling against a harsh society” leave some serious gaps of examination of human experience

- that white middle-class modern women’s life experiences (one of those missing pieces) are not just fluff (shopping and fucking? really?), and to dismiss them as such is fundamentally sexist

- that regular, ordinary people really do, actually, often achieve happy endings, and this is valid literary subject matter

- that literature doesn’t have to be painful to have great affect on us

- and that taking comfort in things that are uplifting can actually lift us up, and that has value

If you change the lens on the microscope by which you analyze writing, both commercial and literary, with many of these ideas in mind, you realize quickly that contemporary literary criticism leaves a lot of worthy writing behind, especially the writing of women.

Mead dissects and dismisses several of Weiner’s books in this piece by refusing to think of them in this proposed new context, instead shoving them under the traditional lens of “The Old-Tymey Rules of What is Good Literature” while willfully ignoring that more and more women are successfully challenging the notion that these long accepted “Rules” have some serious bias in the way of both sexism and snobbishness. That Mead has to reach as far back as George Eliot and Charlotte Brontë to make her case in discussing a contemporary author and her place in contemporary literature says a great deal about how weak her case is.

I can’t imagine how Mead interviewed Weiner, read large sections of the woman’s twitter account, and listened to her speak about women, commercial fiction and the place of both in contemporary literature and yet got Weiner’s voice so very wrong. The woman is not exactly smoke and mirrors; there isn’t a facade there. Weiner’s pretty straight-forward, and it’s impossible to follow her on twitter for any length of time and not come to think of her as self-reflective and open. I can’t imagine how Mead spoke to her and didn’t come away seeing her as genuine, but she didn’t.

Mead also bolsters a wide-spread belief that “Jennifer Weiner has two audiences. One consists of the devoted consumers of her books, which have sold more than four and a half million copies…. Her other audience is made up of writers, editors, and critics.” Even Weiner apparently believes that to be true, and I guess she would know her own audience(s), but I find it hard to believe those two audiences are entirely separate. I definitely bridge that gap.

In the end, Mead decides that Weiner is just whining; that her work doesn’t deserve critical recognition, not because it’s viewed through a sexist and snobbish literary lens, but because of:

the perfunctory quality of some descriptive passages, or of the brittle mean-spiritedness that colors some character sketches. (Readers looking for fairness and kindness will not always find those attributes displayed by Weiner’s fictional creations.)

That was a jaw-dropping statement for me; that same statement could be could be made about sections of work from many contemporary male “literary giants” including Roth, Franzen, Eugenides, Chabon, David Foster Wallace, men who clearly receive great critical recognition, some of it deserved and sometimes not so much.

Mead goes out of her way at the end of the piece to tie Weiner back into her place as “chick lit” by describing in detail the women who come to have their books signed, and how they measure her books against what Mead clearly considers the irrelevant minutia of their own lives, an ending I found as lazy as most of the article.

Winner Winner, Turkey Dinner – 2013 NaNoWriMo Finish

50,119 Words, validated, means that I “win” National Novel Writing Month. I’m very grateful to Stephanie, who has been really supportive of me doing this, even though she’s had a lot of difficulties going on right now. We’re adjusting to her lengthy commute to her new job and a family illness, so it’s been a hard month, but she has been my cheerleader the whole time.

I still have a couple chapters to write, but I’m definitely closer to a finished product than I was in my last two winning attempts. And there is lots of editing to be done, in addition to finishing chapters. But I think this is the most satisfying win I’ve had of the three. This is one I think I might have a shot at getting published some day soon. It’s got some topical stuff in it, so if I want it to actually mean something, I have to get it done and try to get it out there.

Good gravy do I have a lot of television piled up on the DVR to watch.

Conceit via. Wikipedia

via Wikipedia, Conceit:

In literature, a conceit is an extended metaphor with a complex logic that governs a poetic passage or entire poem. By juxtaposing, usurping and manipulating images and ideas in surprising ways, a conceit invites the reader into a more sophisticated understanding of an object of comparison. Extended conceits in English are part of the poetic idiom of Mannerism, during the later sixteenth and early seventeenth century.

Metaphysical conceit

In English literature the term is generally associated with the 17th century metaphysical poets, an extension of contemporary usage. In the metaphysical conceit, metaphors have a much more purely conceptual, and thus tenuous, relationship between the things being compared. Helen Gardner observed that “a conceit is a comparison whose ingenuity is more striking than its justness” and that “a comparison becomes a conceit when we are made to concede likeness while being strongly conscious of unlikeness.” An example of the latter would be George Herbert’s “Praise,” in which the generosity of God is compared to a bottle which (“As we have boxes for the poor”) will take in an infinite amount of the speaker’s tears.

An often-cited example of the metaphysical conceit is the metaphor from John Donne’s “The Flea”, in which a flea that bites both the speaker and his lover becomes a conceit arguing that his lover has no reason to deny him sexually, although they are not married:

Oh stay! three lives in one flea spare

Where we almost, yea more than married are.

This flea is you and I, and this

Our marriage-bed and marriage-temple is.When Sir Philip Sidney begins a sonnet with the conventional idiomatic expression “My true-love hath my heart and I have his”, but then takes the metaphor literally and teases out a number of literal possibilities and extravagantly playful conceptions in the exchange of hearts, the result is a fully formed conceit.